WEEK 1

READING & REFLECTING

Human-Machine Memory website

Semester 1: Recap

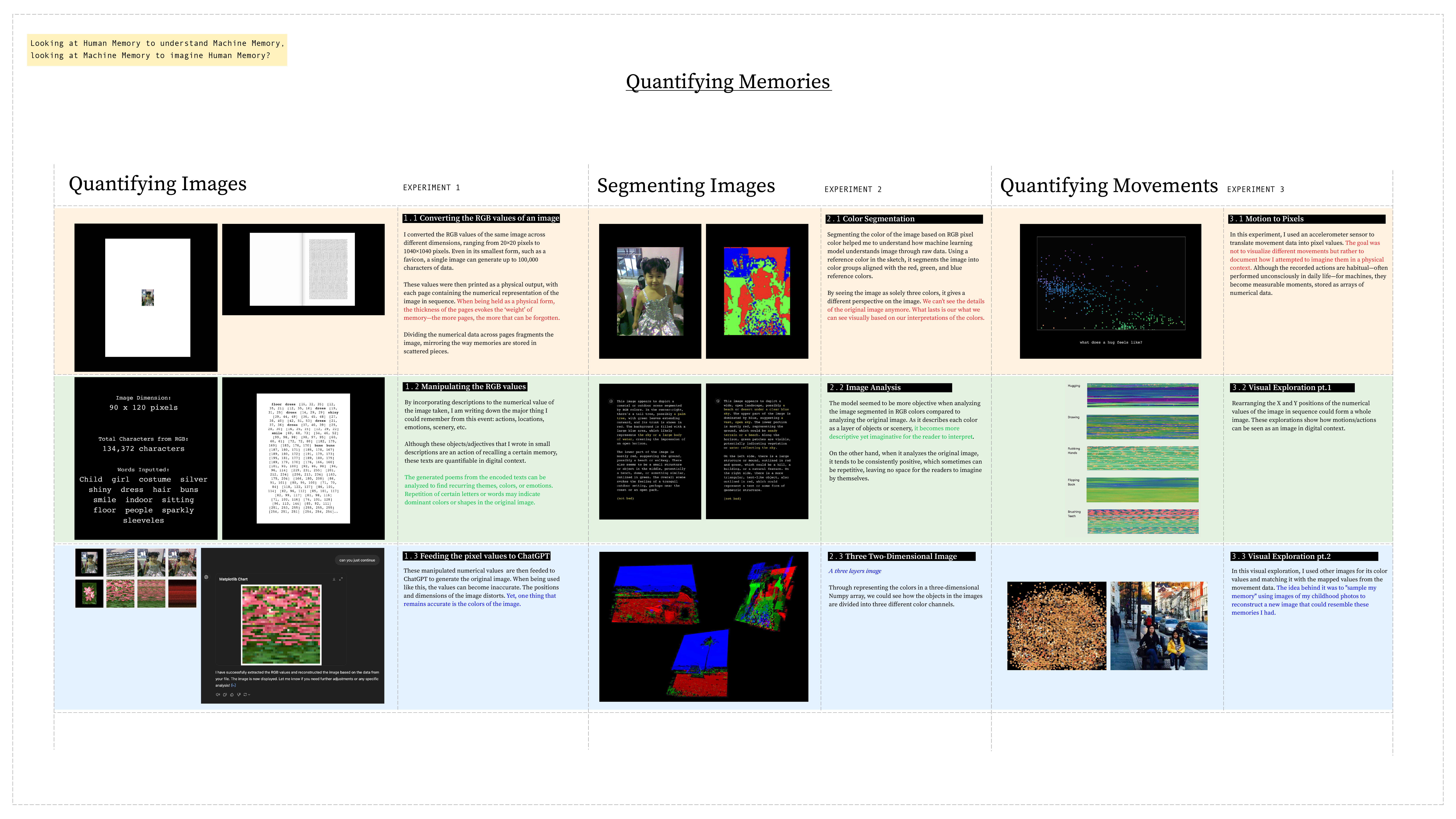

Looking at the proposed ‘Prototype’, The Web as an Exhibition Space, there is a lack of context. There are many improvements that could be made. The navigation is unclear, and the narrative behind the project is not shown well enough. This could confuse the audience about what the boxes are, which box to click first, and what the numbers on the boxes mean.

Since most of the experiments focus on different aspects of what constitute a memory in the digital space and using different techniques to contrast with machine memory, they are somehow not in sync when compiled together, making it hard for people to understand the flow of experiments as well as the purpose behind these experiments.

What could have been done better?

[1] To create a more engaging narrative between the concept and the reader. Reflecting on this, I have considered that adding an external input from the audience might not only add another layer to the work but also bring value to other people. What are the inputs that I can gather from the environment (living or non-livings) that can used to create a participatory experience?

[2] Another idea was to extend from one of my experiments. It doesn’t have to be participatory, rather it could be like an investigation, a scientific research-like (almost like a report) of me trying to retrace my own memories by looking at machine memory (reverse-engineer).

One thing I realized about my experiments is learning about machine memory can teach us about human memories. As I tried to generate different outcomes through these different approaches, and sometimes it can be quite imaginative, I also found the different ways to retrace and recall these memories.

Small CaseStudies

During the semester break, there weren’t any makings done. However, I had some few insights from the readings I collected that I want to share that might contribute to my next steps.

On Community Memory by Mike Tully

Community Memory Project

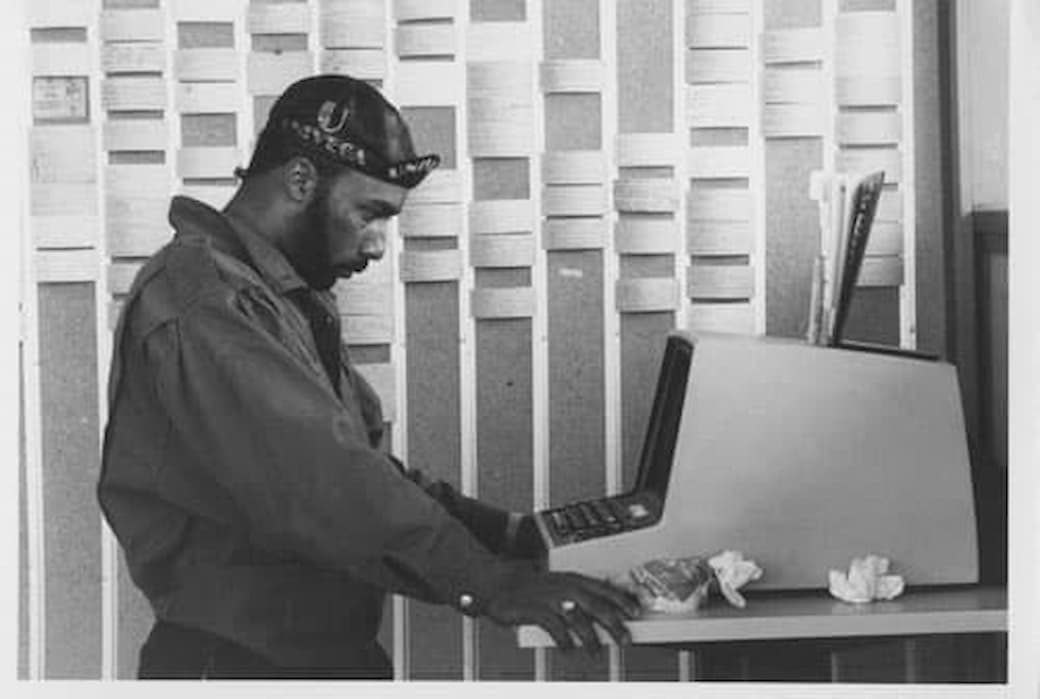

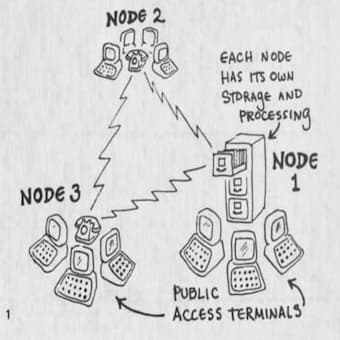

The idea of community memory project stems from the need to make computers accessible to the general public. During that period of time, in the early 1970s, computers were only found in government agencies and research institutions. This born non-profit community, initiated by a former student of Buckminster Fuller, eventually build up their ambition to exchange information and resources within community, and what it calls as a Community Memory Project.

By putting a publicly accessible computer in different spaces, which at that time was called as “terminals”, people are able to place messages in the computer, and retrieve messages through the memory for a specific notice. From what it seems to exchanging within a small community, the project explored how an information portal could be a shared experience, an exchange between participants in which the information circulated was as expansive as the community itself.

“For many people who encountered the initial terminals, it was their first experience with a computer, and they made use of them in unexpected ways.”

What makes this project interesting is how tools can be put to use in service of people, with people using these tools in unexpected ways. It also deals with space, where different locations reveal different origins and interactions through their stories.

The Community Memory Project is like the present internet but its smaller in network scale and localized. Although the present internet offers a vast database of information where we could easily access anywhere and at anytime, the Community Memory Project has something that the internet doesn’t have: a tangible space.

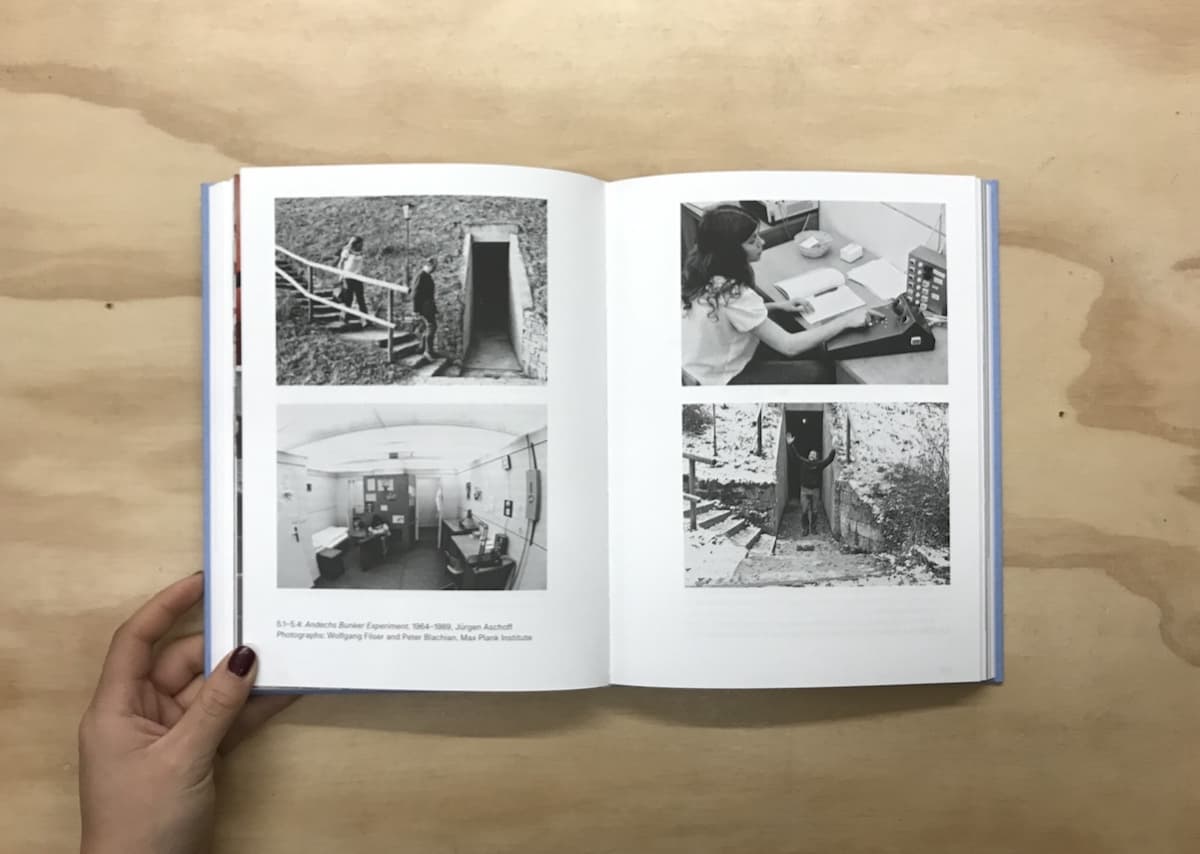

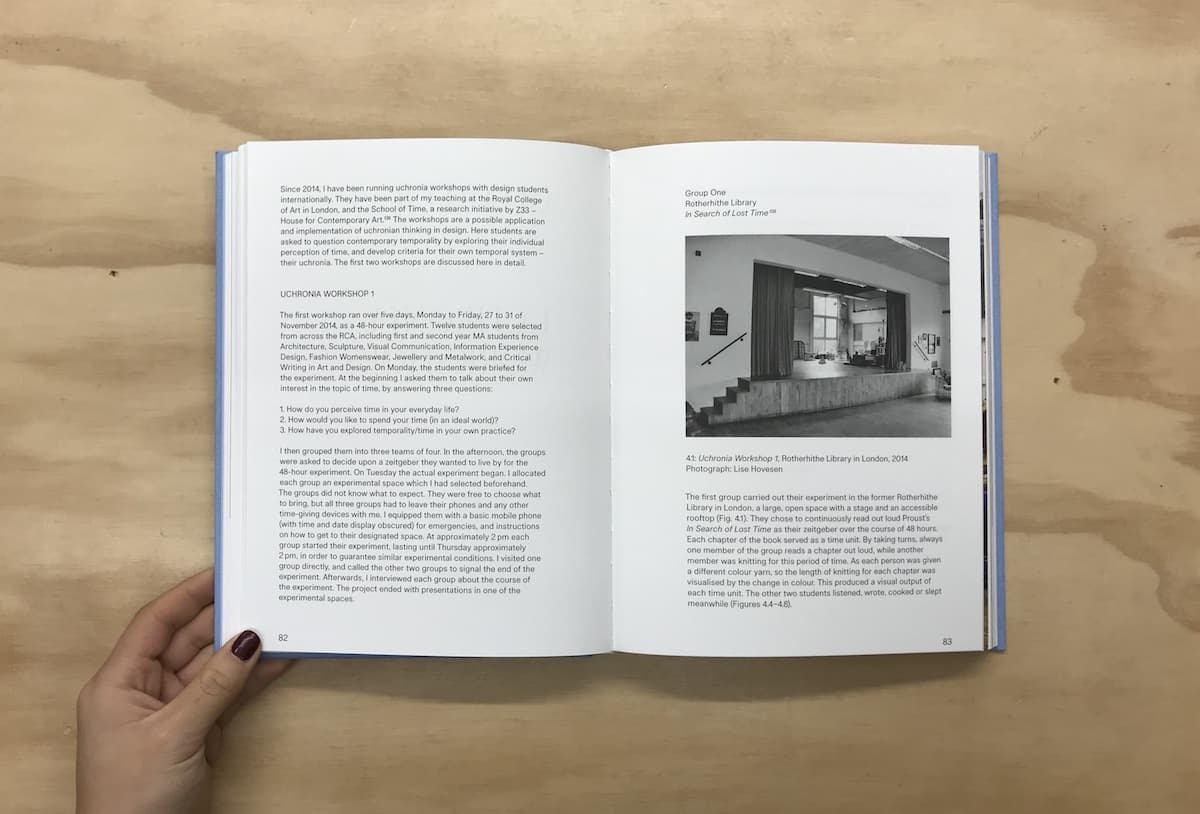

Uchronia: Designing Time by Helga Schmid

Uchronia: Designing Time

Designing Relationship With Time

This book critically investigates the potential risk that arises from our perception of time by looking at the concept of uchronia — a term derived from the Greek u-topos and meaning "no time" or "non-time". The shift from analog to digital time has influenced our temporal existence and reconfigure how we understand and use time.

In the digital age, where time has become more fluid due to technological advancements, Schmid argues that the embodiment of rhythm and speed in digital life has intensified our sense of time pressure and scarcity. As Schmid notes, “this mechanical time seems slow compared to the high-speed age we currently inhabit.”

She draws on Mumford’s notion of mechanical time (Mumford, Technics and Civilization), describing it as a "foreign time" that disassociates time from society. Human life, in contrast, follows its own natural rhythms—such as the pulse, breath, mood shifts, and daily activities—measured not by the calendar but the events that occupy it.

I believe that this situation—the perception of “scarcity of time”—is still common in present days. In a fast-paced network society dominated by Big Tech and AI-driven progress, growth, utility, and performance, time has nearly become blind. Schmid’s discussion of time scarcity led me to reflect on how modern technologies have distanced us from our lived experiences. Just as a ticking clock is a foreign time that measures the human life, a machine-learning model functions as a kind of time machine—everything that exists and expressed in the internet makes up the model.

This brings up the question: in a world where nearly everything is quantifiable, how can we reimagine our relationship with time through machines?

Perhaps revisiting Mumford’s idea of the human body clock as a tool offers a valuable alternative—one that could inform my exploration of trying to “quantify memories” in a more meaningful way.

Reflection

In reflecting my next steps, I gave a challenge for myself to answer a question that often I overlooked.

What is the purpose of my work?

As I reflect on this question, I ponder more to why am I interested in the idea of memory itself.

The concept of memory itself is abstract, and to be able to tell a narrative to what I have researched about what memory is and learning it through machine memory has been a challenging process.

Understanding memory is, at its core, a way of understanding human experience. Even in my past works, I have been drawn to incorporating emotions and poetic interpretations, using art as a means to express intangible ideas. Engaging with a concept as intricate as memory has allowed me to open up new ways of interpreting and reimagining ideas.

Moreover, memory is deeply tied to time, and I believe there is an urgent need to rethink our relationship with time itself. As we navigate the rapid advancements of the digital age, it becomes increasingly important to reflect on what we consider valuable as an experience—especially when human qualities are becoming more easily replicated through technology.

For me, this project is more than just a technical exploration of human and machine memory. It is also a personal journey—one that allows me to retrace my own memories, weaving together thought, experience, and reflection in an attempt to better understand both myself and the evolving nature of memory in the digital age.

References

—-“On Community Memory | Are.na Editorial.” Are.na, 19 May 2022, www.are.na/editorial/community-memory. Accessed 2 Feb. 2025.

—-Schmid, Helga. Uchronia. Birkhäuser, 20 Jan. 2020.